Level playing field can lead to profitable, green steel

Sponsor: Name

Credit: CELSA Steel UK

The UK Energy Security Strategy in April granted the long-suffering steel industry a huge fillip – 100% state compensation for onerous indirect carbon costs, – enabling steelmaking from Hartlepool to Llanelli to become more competitive. Now the industry needs to create a market for ‘green steel’ and it could be a standard bearer for levelling up.

Will Stirling

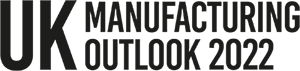

34,000 people are employed by the UK steel industry, with its workers earning up to 45% higher wages than the national average. Credit: UK Steel, part of Make UK

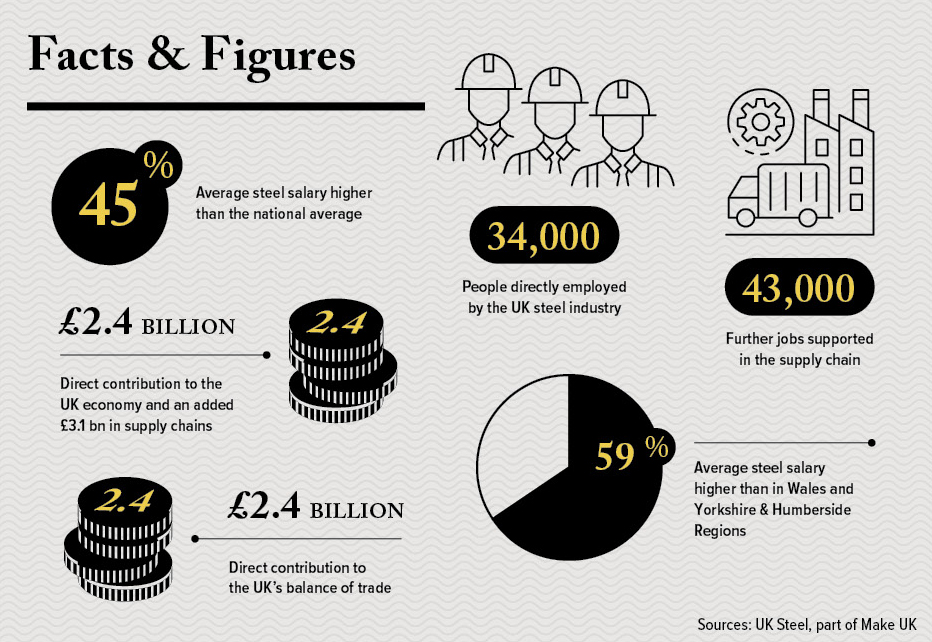

Great Britain produced 7.2 million tonnes of steel in 2021 (there is no steelmaking in Northern Ireland), the lowest quantity since a 10-year high of 12 million tonnes in 2014. Steel production here has fallen to eighth in Europe, behind Austria and Belgium. To many that trend supports the image of yet another heavy industry in inexorable if gradual decline as these ‘old, smokestack industries’ – coal, oil, petrochemical, the internal combustion engine – give way to new high-tech and greener industries.

But think again. Steelmaking is packed with intelligent research and development, is becoming much greener, its workers earn high wages (avg. steel pay is 45% higher than national avg.) and is fundamental to the performance of numerous other sectors from construction and carmaking to aerospace and rail. Rather than being old and defunct, the future is very bright: and in large part due to its nemesis – energy costs.

Steelmaking got a huge boost in April when the UK Energy Security Strategy gifted it a lifeline. Rewarding years of lobbying to help British steel compete on par with its European neighbours, the government will pay 100% compensation for the indirect cost of carbon within electricity prices, costs that had hampered the industry for years compared to France and Germany, which pay 34% and 38% respectively less for their electricity (see chart). Compensating for the indirect carbon costs brings UK steel a step closer to a level playing field in the global market.

And that’s not all. The strategy also said the government will consult on providing the same exemption for the levy paid for legacy renewable electricity. “If it addresses both the carbon cost and renewable costs in the bill, then this gives us an opportunity to engage with government in partnership and, moreover, it may prompt the will to tackle the four elements of electricity that kill profitability,” says Gareth Stace, director-general of UK Steel, the industry group that represents the sector. Steelmakers in Britain face several components of electricity cost: wholesale costs (ex-carbon), policy costs which consists of carbon, renewable energy and Capacity Market costs, and network costs, including distribution.

Lowering energy prices would be welcome by any sector, especially in 2022, but it could galvanise steelmaking by more than just improving competition, as it would pave the way for green steel. ‘Net carbon zero’ may be hard to fathom for a business that, weight for weight, is more electricity intensive than any other (possibly fertiliser is close). But these lower costs of energy are the catalyst needed to go green, and the government now understand this much better, says Stace.

China manufactures 900 million tonnes of steel a year, almost 50% of global production. When Stace joined UK Steel in 2015, the Chinese had been running excess capacity for its domestic needs for four or five years, ‘dumping’ cheap steel on Europe. British industry bought the under-priced steel and local mills suffered. “For reinforcing bar, China had 0% of the UK market in 2010-11; by 2015, that had increased to 43%,” Stace says. Government then reversed a long-held policy to allow free trade in steel and voted at the European Commission to hit Chinese product with tariffs. It was a sign that the government really understood the economics of steel and its importance to the UK.

Disruption leads to leaner sector

Over the next few years, the steel sector changed radically. Greybull Capital bought Tata Steel’s long products division, based at Scunthorpe and Skinningrove, which became a new company, British Steel in 2016. This was acquired by Chinese steelmaker Jingye Group in 2020. Tata Steel sold off other divisions to Sanjeev Gupta’s Liberty Steel, that is now shifting its footprint, in April announcing investment in its Rotherham plant but plans to cut 200 jobs at sites in Stocksbridge and West Bromwich. The Ministry of Defence bought Sheffield Forgemasters in July 2021 for just £2.6m and pledged to spend £400m over the next decade upgrading equipment for military capacity, like reactor pressure vessels for nuclear submarines.

At the same time, lobbyists like UK Steel and the industry explained to government that energy prices were 50% higher for UK steelmakers than those in France and Germany, and business rates these UK companies paid were five to 10 times higher than in parts of Europe.

“In those early days of reform, government almost didn’t believe the disparity,” says Stace. “So, we have highlighted the gap between us France and Germany in an annual report for the last five years.” As an indication of the gap in alignment between state and steel, the Treasury had suggested the sector receive corporation tax relief – until it was shown there was little profit to tax.

The penny has now dropped. The effect of the 100% EII compensation scheme means, Stace says, “that from April 1 2022, the steel industry will be paying up to £21m less for all its electricity.” Lower cost of production, as well as a better market price, means the sector can target net zero. The route to a practicable net carbon zero industry is not through taxation but by investing in carbon-saving technology and R&D, and harnessing more renewable energy in steelmaking.

Decarbonisation will boost industry and create jobs

The UK Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy, released by BEIS (Department for Business) in March 2021, targets a near completely decarbonised steel sector by 2035. To help fund this, the government announced a £250m Clean Steel Fund in 2019, which is in jeopardy as the funding has not been confirmed, and investments to reduce emissions are on hold until 2023 because of “the absence of a clear roadmap for decarbonisation”, says Roz Bulleid from the policy group Green Alliance (reported in Energy Monitor).

One route to emitting less carbon is to invest in more electric arc furnace steel production. This process still requires vast amounts of electricity to power the electrodes to melt used steel, but is less dirty than the blast furnace process, whose chemical reactions produce large amounts of carbon monoxide. Britain already has a high proportion of electric arc furnaces (EAFs), at Celsa in Cardiff, Liberty Rotherham, Outokumpu and Sheffield Forgemasters. But more EAF is no panacea for long-term green steel, as the large integrated steelworks – the plants that use Basic Oxygen Steelmaking and typically make flat steel – are essential to Britain. The carmakers, white goods companies, container makers and other industries that need flat, rolled steel with precise properties either cannot or would not source steel from EAFs, because the process is unsuitable and can create impurities.

To transform UK steel into a net carbon zero industry we will have to create a market, and that needs push and pull, says Stace. Pull from the market, where customers like architects and builders increasingly want low carbon steel as environmentally-sound construction is both preferred and being legislated. The push is an incentive from government. Other cheap steel will always tempt buyers without legislation. “After investing millions to achieve net-zero steel, the customers may not care about the carbon content; this Turkish or Chinese steel is much cheaper so we’ll buy that,” says Stace. The government would have to say that by 2035, or a sensible deadline, we won’t allow you or penalise you for buying carbon-intensive steel. This creates a market to aim for.”

Levelling up

Back to the image of steel as old or future industry. In fact, steel is an enabler for ‘levelling up’, the phrase coined to bring more prosperity to deprived areas. There are about 34,000 people employed directly in the steel sector and approximately another c. 43,000 jobs supported in the supply chain, plus the multiple of indirect jobs servicing steel companies. “Nearly all these companies operate in the regions where the Prime Minister wants to level up, and their employees earn 40% to 45% more than the average salary in those areas,” says Stace. “If you really want to level up look no further than the steel sector to achieve that.”

Stace adds that with lower energy costs, a state-supported green steel market, and knowing global steel demand has increased year-on-year for years, “why shouldn’t we look to produce and export more steel too? To supply more steel into the UK market, European markets and the global market. India is massively ramping up its steel exports – we should too.”

“One route to emitting less carbon is to invest in more electric arc furnace steel production”

Liberty Steel is investing in its Rotherham plant but cutting jobs at Stocksbridge. Credit: Liberty Steel, Brinsworth.

“Steel is an enabler for ‘levelling up’, the phrase coined to bring more prosperity to deprived areas”

Above/Below: The steel industry needs to make greener, low carbon steel to capture more global market share. Credit: CELSA Steel UK