Rail Industry Needs Stability to Stay on Track

Sectors: Rail Industry

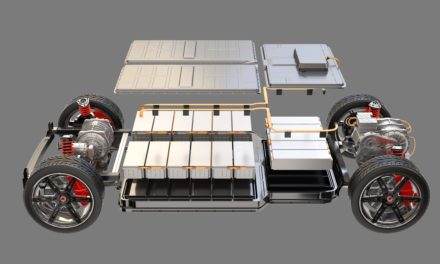

Above: Hitachi Rail and Eversholt Rail are in the advanced stages of designing and engineering an electric-diesel-battery (tri-mode) train, with plans to trial on a Great Western Railway Class 802 train in 2022. Credit: Hitachi Rail

Despite signs that the government supports an expansion of the rail network, there is still concern within the industry that a policy of boom and bust will cause supply chain difficulties.

Christian Wolmar

Featured image caption

The rail industry craves certainty. Unfortunately, this is greatly lacking at the moment and this failing is having a negative bearing on the rail manufacturing business.

On the face of it, things are relatively rosy. Yes, Covid reduced rail use to a mere 5% of normal during the first lockdown and it has remained below pre-pandemic levels ever since. Inevitably that has had an impact on the supply industry as the near-continuous quarter-century of passenger numbers increasing came to an abrupt halt.

However, there are good signs of a recovery, at least among leisure and off-peak passengers, if not commuters. More important, the government has demonstrated a continued commitment to the industry with the announcement of its modified version of the eastern arm of HS2 in November 2021.

This Integrated Rail Plan promises to put nearly £100bn of investment into the industry and will ensure there is still significant demand for new trains and all the rest of the equipment needed for new railways. Additionally, there are numerous major schemes in the pipeline to improve the existing passengers and freight infrastructure that, in turn, will result in considerable orders for the manufacturing industry.

An ‘unsatisfactory’ timetable

Indeed, there are now four manufacturing bases for rolling stock in the UK, the most since the industry was privatised in the 1990s. At one point only the Bombardier plant in Derby survived and even that was under threat until the order for the Crossrail trains came through nearly a decade ago.

Since then, there has been a remarkable resurgence with orders for thousands of train carriages which has attracted three other producers to Britain’s shores – Hitachi in the North East, CAF in south Wales and Siemens in Yorkshire.

But that massive upsurge, according to David Clarke, technical director of the Railway Industry Association (RIA) which represents more than 300 companies in the supply chain, is part of the problem.

The figures demonstrate a remarkable swing between boom and bust. In the initial years following privatisation in the late 1990s, there was a gap of more than three years without a single order, followed by half a dozen boom years culminating in more than 1,000 carriages being ordered in 2002. Then a decade with nothing, followed by another six years of boom, with a recent return to bust.

Clearly, this is a completely unsatisfactory pattern but what would Clarke like to see? “I would be quite happy with an overall level of orders if it were steady, giving the industry stability,” he says.

He points to Germany where a recent order for more ICE high-speed trains is a clear response to fears of a post-pandemic recession. “The ICE order represents options being taken up by Deutsche Bahn made at the time of the initial order,” he notes. “That ensures a level of stable demand that we simply never have.”

Clarke points out that in the UK when trains are ordered, there is no associated level of options to be taken up at a later time. “This would not only ensure stability, but it would mean the trains cost less as the price would be guaranteed at the time of the initial order,” he explains.

This is reflected in other aspects of the rail manufacturing industry, notably electrification and signalling. Rolling stock is the most visible part of the rail manufacturing base, but work on the track also requires considerable equipment, such as masts for the overhead wiring, the cabling itself and electrical equipment for signalling as well as power.

Here too, it is proving hard for the industry to plan ahead as there is a lack of clarity about the government’s intentions.

Government hesitancy risks investment

Investment by Network Rail is governed

by five-year Control Periods, a concept

rather redolent of the old Soviet Union’s planning system. The money available for

each five-year period is determined through

a process of negotiation with the Office of Road and Rail.

The current Control Period, CP 6, started in April 2019 but the pipeline of work, which includes major enhancements as well as maintenance, has been held up by the government’s failure to produce a list of what schemes are to be prioritised.

The government originally promised that this would be published in the autumn of 2019 but more than two years later, the industry is still waiting for the list of projects. This is made all the more urgent by the fact that the precise nature and timing of projects in the government’s Integrated Rail Plan, which includes electrification of the Midland Mainline and upgrading the route across the Pennines, has not yet been determined.

The programme should also contain schemes about increasing freight capacity in Cumbria and for the Heathrow Western Rail Link which will connect Reading with a direct train service to the airport. The status of many of these projects is now uncertain. RIA hopes that the programme will at last be published by the end of 2022, giving the rail manufacturing industry a little bit more of the certainty it needs.

Clarke recognises that the rail manufacturing industry is dominated by huge multinational companies that produce trains and other equipment across the world. However, he points out that if there were a more consistent approach to keeping order books ticking over, then these firms would, like the rolling stock companies, establish bases in the UK, creating jobs and quite possibly even increasing exports.

The importance of having a strong national base was emphasised when, in March 2022, the government announced that its Export Credit Guarantee scheme was backing a €2.1bn loan to fund construction of 503km of high-speed electric railway in Turkey.

According to the announcement, it is expected that “nine-figure contracts [are] set to be

awarded to UK rail suppliers as a condition of UK support”. This is a breakthrough since over the past two decades, there have been very few foreign orders from UK-based manufacturers. RIA is confident that this large order will be the first of several more. l

News in Brief

- Cable harness, wiring looms and panel assemblies specialist, Teepee Electrical, is targeting a 20% boost in sales after securing a string of new contracts, including one with a major rail customer for an on-going fleet upgrade project

- The Black Country business, which supports customers in the rail, automotive, ‘blue light’ and electrification sectors, is looking to take turnover past the £3m mark and has recently invested £100,000 in new tooling and machinery. “Sales are back to £2.5m, which is where they were before the pandemic struck. The really exciting news is that we’re currently witnessing our biggest pipeline of opportunities, and this could easily translate to more than £500,000 of additional business over the next 12 months. “If things go as planned, I’d expect us to create three more jobs taking our total workforce to over 50 staff – our employees have been superb during the pandemic and the real heartbeat of the business,” says managing director Steve Clarke.

- Thales has installed a ‘rolling lab’ on the UK railway network to provide critical data on a hyper-accurate train positioning system that aims to further increase the safety and efficiency of Britain’s railways. “We have dozens of applications we want to investigate over the coming years to quickly test viability and conduct proof of concept demonstrations. Particularly usefully for this initial train is that we will be able to continuously generate and analyse data as it runs in passenger services, so it lets us test ideas at a low cost and high speed. “It gives us a much quicker way of responding to customer needs and demonstrating solutions,” says product line manager Alex Stockill.

“There are now four manufacturing bases for rolling stock in the UK, the most since the industry was privatised in the 1990s”

Above: HS2 works in the Midlands. Credit: Network Rail

“Rolling stock is the most visible part of the rail manufacturing base, but work on the track also requires considerable equipment”

Above: Vivarail was responsible for the UK’s first battery-powered train exported to the US to launch a new type of affordable ‘Pop-Up Metro’ service, with more orders expected. Credit: Vivarail

“The rail manufacturing industry is dominated by huge multinationals”