Amidst the Gloom, Electric Switch-Over Offers Hope

Sectors: Automotive

The auto sector continues to be a shining light of the United Kingdom’s manufacturing industry, despite having to contend with numerous hurdles. The EV revolution promises significant growth opportunities, but political backing needs to equal industry ambitions.

Professor David Bailey

With 2021 well behind us, the automotive industry hoped that 2022 would see an acceleration in production and sales as supply chain constraints eased in terms of the ongoing semiconductor shortage.

That supply chain bottleneck still casts a shadow over the industry. Recall that when the auto industry ground to a halt in early 2020 when Covid hit, many auto firms cancelled semiconductor orders.

And when the industry restarted much more quickly than expected later that year, it found itself at the back of the queue for semiconductors. Meanwhile, demand for chips had soared with home working, the growth in home entertainment and the ‘chips with everything’ nature of the internet of things.

As a result, output and sales were down in 2021 due to ‘long Covid’ supply constraint shortages. The overall hit to global auto output was around 7.5 million units. It was hoped that 2022 would be a better year as new chip capacity came on stream.

But the Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought with it some profound economic fallout in addition to the appalling human consequences of war. Sanctions on Russia have made trading there more difficult, and cars firms like JLR suspended sales in Russia so as to ‘do the right thing’.

Cars are the UK’s biggest export to Russia and the West Midlands is the biggest exporter. Such sales volumes may be low, but the cars sold are often high-end JLR SUV models with big margins. Overall, it is another blow for the premium and luxury British brands.

The big increase in energy costs also pushes up manufacturing costs. And supply chain issues are likely to persist as the war in Ukraine brings new challenges.

For example, Russia and Ukraine are major producers of high-grade neon gas used in making semiconductors, so the chip shortage is set to continue. Meanwhile, Russia is a major producer of palladium, used in catalytic converters. Moreover, Ukraine is a major hub for making electrical wiring loom harnesses.

The latter requires low costs and high skills. Harnesses can be sourced from other countries (notably from Turkey and North African countries) but those harnesses are bespoke for each model, and finding new suppliers takes time. As a result, several factories across Europe have been on part-time working, including the MINI plant in Oxford.

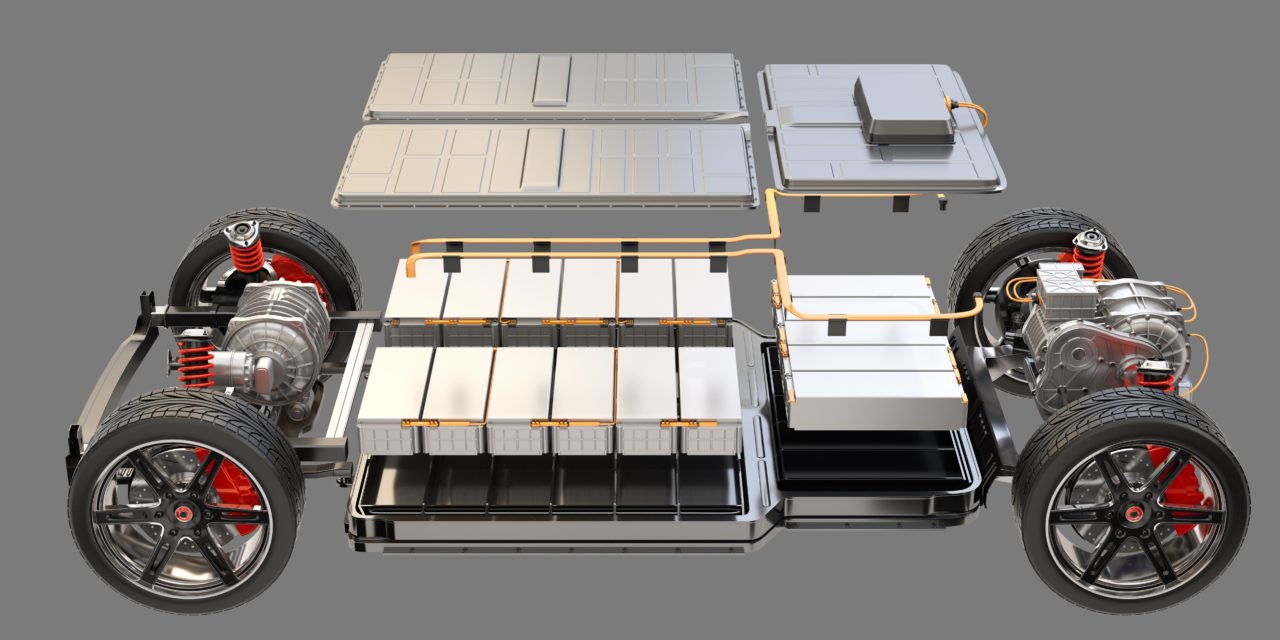

The chip shortages and supply chain issues have brought into sharp focus auto makers’ reliance on critical components as the industry transitions to EVs. Automakers are increasingly looking at forming JVs with makers of batteries, chips and E-drive units, or to bring production in house. That may see more automakers like JLR making

key components like e-drives in-house rather than buying them in.

Beyond supply chain issues, the UK is set to experience the biggest squeeze on living standards since the 1950s. A mix of cuts to universal credit and rises in national insurance contributions and council taxes will combine with rapidly rising prices and a massive hike in energy costs (again linked to the war). Inflation could easily reach double figures, with the Bank of England raising interest rates.

As a result, the UK economy is entering a period of ‘stagflation’. That will dent demand for big-ticket items like new cars even with a hang-over of pent-up demand from supply constraints.

Consequently, 2022 is set to see supply chain issues eventually giving way to demand-side constraints as the cost of living crisis bites. And don’t forget the ‘slow burn’ drag on UK economic growth from Brexit.

Where does this leave the auto industry? While output will be up on the 75 million units made globally last year, reaching something like 81.5 million units, that figure is around 2.6 million lower than originally forecast.

Here in the UK, output slumped to under 1 million in 2020 and barely improved in 2021. It could recover to something like 1.2 million this year. That is still way below the 2016 peak of 1.7 million.

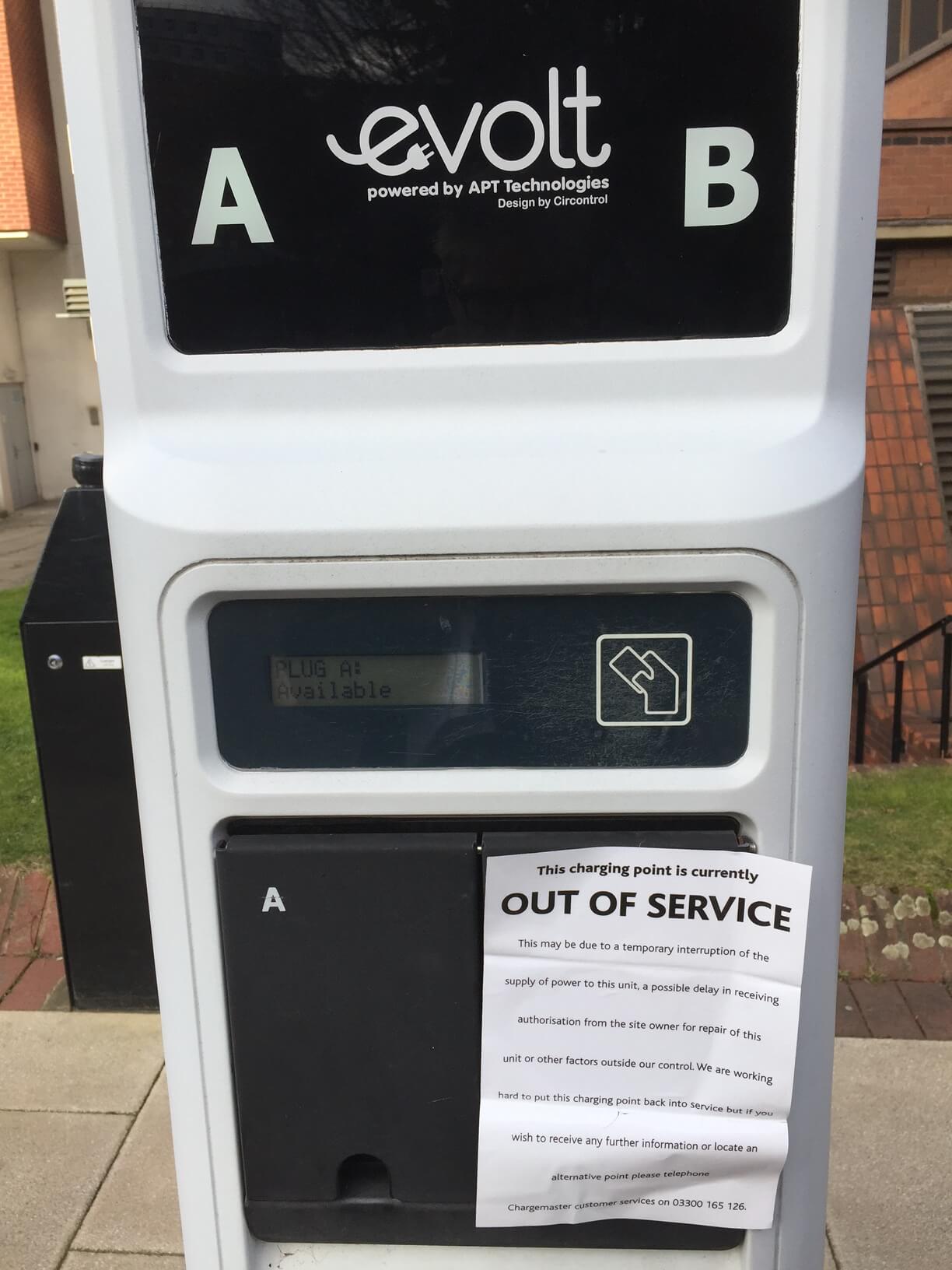

Longer-term output could get back to 1.5 million by 2030 and 1.7 million by 2035 but that will require much more of a supportive industrial policy than seen at present and a huge effort to switch both the demand side and supply side over to EV production. For example, a major effort to roll out new charging infrastructure to keep pace with EV take-up is needed, given the ‘charging anxiety’ felt by EV drivers.

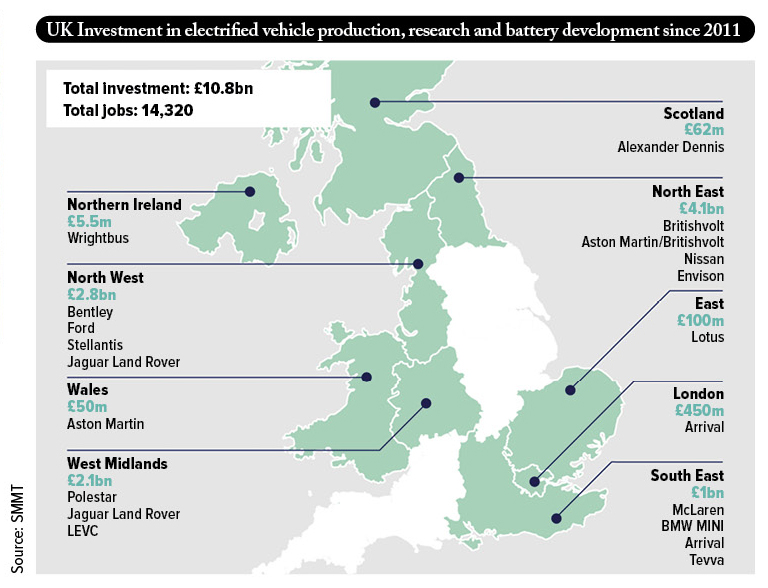

Indeed, amidst the general gloom, hope lies in the big switch to EVs. Around one in four cars sold in the UK in 2022 will be a plug-in, and the UK auto industry is rapidly switching to making electrified vehicles. Nissan, LEVC, MINI and Jaguar already offer EVs (although not all are made in the UK). And JLR, Nissan, Stellantis and Lotus have all confirmed investment in EV production in the UK.

The UK has been lagging behind EU countries in terms of investment in the large-scale battery manufacturing that will be needed to underpin volume manufacturing but we have a least seen a start. Nissan’s partner Envision is investing in a new Gigafactory near the Sunderland plant. Start-up Britishvolt has overcome all the odds so far and has brought in major investment to build a new Gigafactory, also in the North East. Next, it will need to find customers.

A decision by JLR on its battery partner could stimulate the building of another Gigafactory in the UK. Envision is in the running for this and while it will look at a range of sites across Europe, JLR will prefer British sourced batteries if at all possible. That may mean another win for the North East given its availability of cheap land, policy support via a freeport and sources of green energy.

What’s hugely encouraging is how a mix of big and small British-based firms offer hope for the big EV switch over. For example, taxi maker LEVC (owned by Geely) is diversifying into commercial vans in what will be a huge market. Meanwhile, tiny RBW classic electric cars near Lichfield is producing stunning new MGBs powered by Continental EV drivetrains.

Moreover, RBW has developed a modular system for converting classic cars to EV power. This is surely set to a huge market going forward. Just think that there are over half a million classic Ford Mustangs in the United States, as well as many classic British sports cars down the ages here in the UK. Converting just a fraction of these offers a big new market.

And London-based EV maker Arrival is a leader in the development of EV commercial vehicles, including vans and buses, with production to be based on a ‘micro factory’ model. Their EVs are underpinned by a scalable EV platform so as to make multiple vehicle models. Backed by the likes of Hyundai, Kia and BlackRock, it listed on NASDAQ via a SPAC. Last year it announced it would move into making ‘ride-hailing’ cars for Uber.

Big supply chain and demand-side challenges loom for the UK auto industry. It took a profound hit from Covid and Brexit combined (notwithstanding the very welcome Trade and Cooperation deal with the EU). But what is left of UK auto is highly productive, high quality, internationally competitive and boasts a superb design base.

That offers a resilient foundation on which to build as the EV revolution unfolds. Big challenges persist, but big opportunities also await. On that, the government needs to do much more to back the industry’s transformation to a low carbon future. It is all to play for.

News in Brief

Silverstone-based Lunaz, which specialises in the restoration and electrification of classic cars, is increasing its production capacity to 110 re-engineered vehicles a year. The 50% increase on 2020 output is in response to surging global demand from a new generation of buyers.

Goole-based emergency vehicle manufacturer, Venari Group, has commenced production on an undisclosed volume of military grade ambulances which will be deployed to Ukraine to support the medics working on the frontline.

BPL Engineering Group has installed one of its largest hydraulic presses to date – a £1m, 600-tonne machine from Worcester Presses. The increased bed size will prove crucial in helping the Kings Norton-based firm target stampings for the automotive, rail and aerospace sector.

“The machine, which was installed as part of a three-month factory reconfiguration project, allows us to target larger stampings in various material grades, including aluminium, mild streel, structural steel, stainless steel, brass and copper,” says Matt Adams, operations director at BPL.

“Cars are the UK’s biggest export to Russia and the West Midlands is the biggest exporter”

Above: Geely-owned taxi maker, LEVC, is diversifying into commercial vans in what will be a huge market

“What’s hugely encouraging is how a mix of big and small British-based firms offer hope for the big EV switch over”

Above: The new electric MGBs in production at RBW’s site in Lichfield

Above: The UK’s ratio of public standard chargers to electric vehicles has rapidly fallen from one for every 16 plug-ins a year ago to 1:32 today